To disclose or not to disclose? And if the former, when, how, and, crucially, why? These questions have nettled me since my diagnosis, on Dec 17 2020, of Autism Spectrum Disorder ‒ or, as I and many other autistic people prefer to call it, Autism Spectrum Condition. Autism might be disabling in a world designed for neurotypicals, but it is not an illness! I have told family and close friends, who have largely all been supportive (sometimes after the odd hiccup of surprise); and I also disclosed at work, to enable me to claim reasonable adjustments if necessary. But although it helped me to share my breast cancer journey online in 2016-17, and I initially wanted to play my part in educating wider society about autism, I kept delaying the moment of public declaration. As the anniversary of my assessment approaches, though, and autistic women are hitting the headlines here in the UK, it feels time to speak this particular truth.

I’ve chosen to do so on my blog, partly because I’ve barely been here since the start of the pandemic, and partly because the news feels too large for even a long Facebook post. Discovering, at the age of 53, that I am autistic, was a life-changing revelation that I am still slowly integrating. Not that it came totally out of the blue. I actively sought the assessment – another less medicalised term I prefer ‒ from my GP, after a long process of learning about autism: at a staff training workshop at the university in 2015, online at the National Autism Society, and through a helpful conversation with the brother of a friend, a professional clinician who told me more about how the condition manifests in girls and women. Initially I felt ‘borderline’, but the more I learned, the more autistic traits I recognised in myself: rather than fitting a stereotype of being ‘non-empathic’, for example, autistic people, especially females, can be hyper-empathic; rather than numbers and trains, the special interests of girls tend to be cats and literature. (Though actually, I get inordinately excited on steam trains . . . ) For reasons that may be part-sociological, girls tend also to mask the condition more effectively than boys, from an early age setting themselves the task of learning the rules of social interaction ‒ a piece of information that shed new light on my love of acting as a (cripplingly shy) child and young teen. Still, when it came, the assessment was a shock. It both made perfect sense and upended everything I thought I knew about myself.

I’ve described the assessment as a magnetic jigsaw puzzle piece at the centre of my psyche – it draws some pieces of my life toward it and repels others (what a relief to not have to feel guilty or inadequate any more over my fear of driving in the UK, or my complete inability to network at conferences!). But while I am grateful for this new self-knowledge, its emergence is a slow upheaval that involves coming to new terms with some painful memories. I am what educator Sarah Hendrickx, herself autistic, calls part of the ‘feral generation’: undiagnosed autistic adults who were just left to fend for ourselves until clinical awareness of the condition caught up with us. In many ways I’ve done well – but the term ‘high functioning’ is misleading. Along with the books and the academic career there’s been a lot of hurt, disappointment, loneliness and alley cat spatting, for most of which I blamed myself. Just last night I was watching Atypical, the Netflix show about a young autistic man and his family, and a lump of recognition came to my throat. Apart from during my cancer treatment, I don’t tend to expose my vulnerabilities over social media – if I’m feeling low I prefer talking one-on-one to friends – so the thought of posting, alongside photos of people’s breakfasts, updates on the autism-related trauma I’ve experienced over the years is chilling.

The answer, I’ve realised, is to be clear about why I am doing this. In some ways, it is less to share my feelings than to explain why often I don’t. I’m not being rude when I avoid social media, or if I post mainly work, travel or politics-related updates. As an autistic person, it takes me longer to process information, so even happily interacting with people can take a lot of time and energy I need for my own work. I think of FaceBook as a 24/7 party, and I just can’t attend a party every day. Also though, I feel that if I were to post about my own upsets, I would then be obliged to respond more often to other people’s, and while I do care, it can overwhelm me to scroll my timeline and read a litany of people’s griefs and struggles. Having made a conscious decision, however, not to be fully emotionally engaged on Facebook, I sometimes end up feeling that I’m creating an online persona that only superficially reflects who I am. Honesty is another autistic trait, and rather than put daily effort into this project of benign dissemblance, I just use social media intermittently, often waiting until I have something good to share – hopefully a live event where I can have the kinds of interactions that are more meaningful to me.

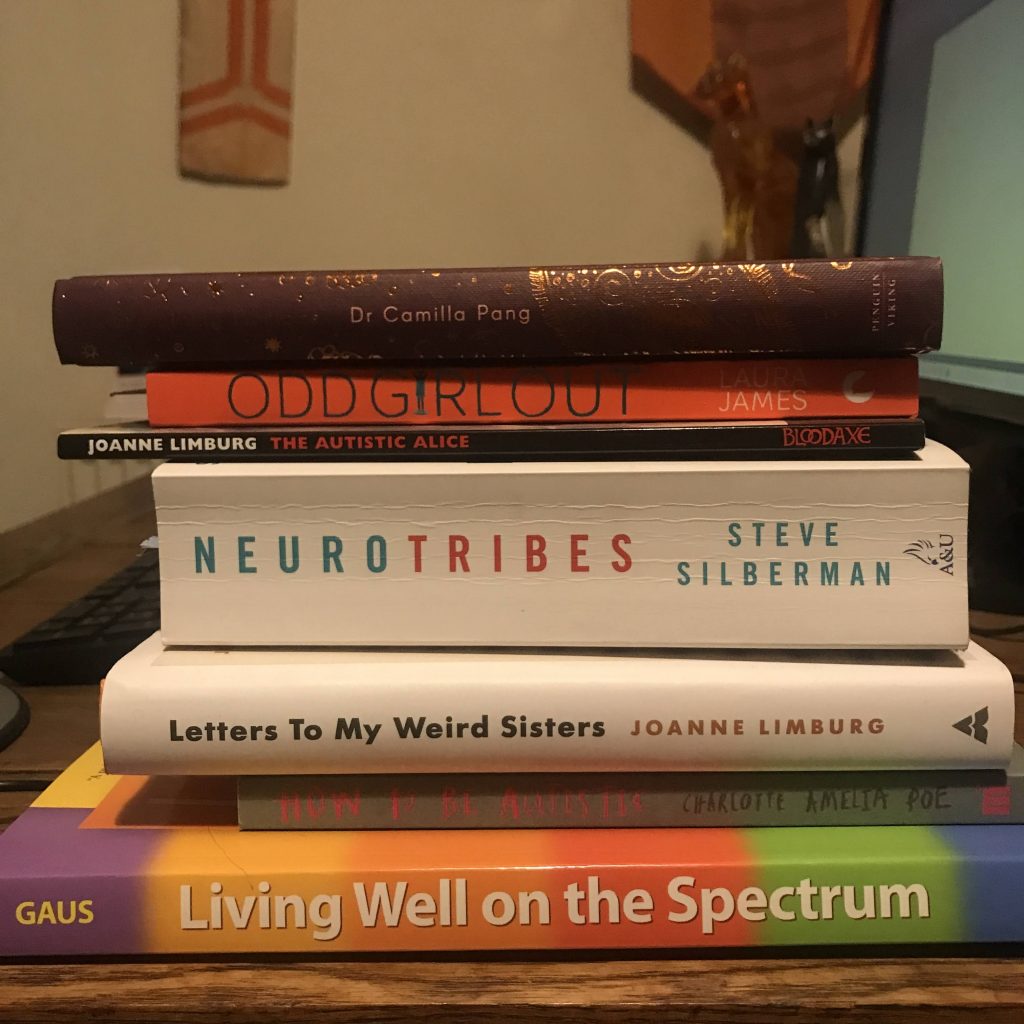

At the same time, I need and value community, or I would have left Facebook a long time ago. I like keeping up with people’s work and life events, and following raging debates, and sharing positive news about the planet – and I hope I’ve been a not altogether terrible friend when others are going through hard times. Having told everyone I can in person, I now want my online and beloved old friends to know about my assessment, and welcome their support, understanding and congratulations! I also want to connect more deeply with the autistic community – including women like Joanne Limburg, whose poetry and prose have been an enlightening part of my own journey this year. I have quite a few already, I must say (us feral autists wouldn’t have survived without somehow finding our tribe) but it will be great to find more ‘Weird Sisters’ and Off the Wall Brothers!

Finally, while I would still like to help educate people about autism, hopefully that will happen organically as part of the process of disclosure. My greatest personal desire as a newly assessed autistic person is to experience more of the strengths and highs of the condition and fewer of the challenges (or less intensely, at least!). Another of my fave new terms is ‘autistic joy’ – for all the social awkwardness, executive dysfunction and physical clumsiness of my existential condition, gosh it is brilliant to be able to amuse myself for hours and hours, or go into spasms of delight at the sight of a tree! (And while I will never be a ballroom dancer, when I saw footage of Greta Thunberg dancing to her own private music, my two left feet and linguine limbs began twitching in time to my own . . .) To conclude with the strength of honesty, in making this public disclosure I ultimately want to be more fundamentally honest about myself online. Perhaps that will lead to greater engagement on social media, perhaps not, but at least I will not be so thoroughly masking who I am any more. Now *that* would be autistic!

Photo credits:

- Rodin, L’Adieu (1892). Sculpture of the head of Camille Claudel. Photo by Naomi Foyle

- Naomi Foyle by Coxy.

- Books on autism, photo by Naomi Foyle